Educating Sommeliers Worldwide.

By Beverage Trade Network

Sommelier Business joins with Nicolas Quillé, MW to create a short wine technical series to give on-trade professionals wine technical knowledge. In this article we write about White Winemaking and Sensory Clues.

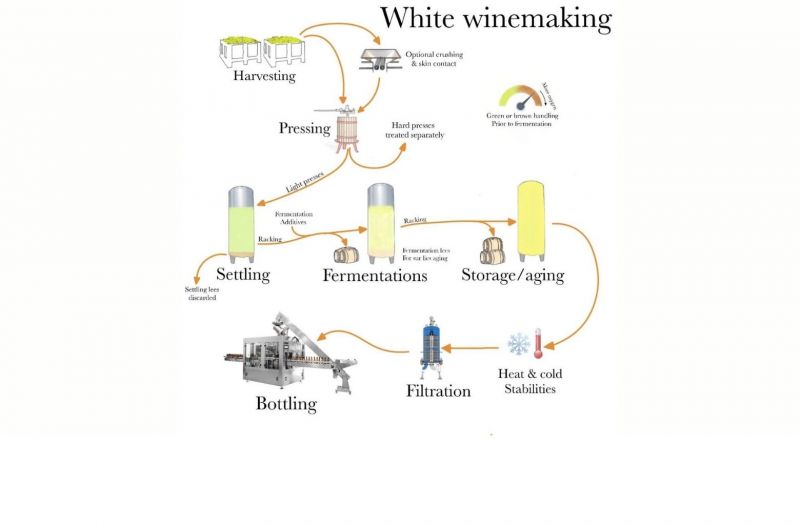

Most grapes have white pulp and extracting their juice quickly means that it will be clear. Picking is done by hand or machine and it is impossible to taste the difference. Hand picking is rarely detrimental to quality and its downsides are that it is expensive, difficult to execute at night and too slow for large picking campaigns. Hand picking is critical for white wines made from red grapes and winemaking that requires intact clusters (carbonic maceration, appassimento). Therefore, while the picking technique cannot be tasted, it can be inferred based on an estimation of how the wine has been made.

Once the harvest gets to the winery the juice must be extracted with a press. Sometimes white grapes are crushed to fit more grapes in the press or to promote skin contact. Skin contacted grapes may be added with enzymes to break skin cells and increase the efficiency of the technique. Skin contact's objective for whites is to release aromas and aroma precursors that are located in or near the skin. This always results in a slight uptick in phenolic extraction which makes the combination of intense primary aromatics along with a slight astringency a reason to suspect skin contact.

Grape pressing yields different juice qualities as the pressure increases. The last juices, or hard press, are always low in acid and high in tannins. The resulting juice must be clarified to remove grape particles because they lead to vegetal and earthy aromas. The reference clarification method is cold settling by gravity for 24 to 48 hours. The lighter settled juice is then racked and the heavier lees are filtered/discarded. Other clarification methods include flotation and centrifugation - they cannot be detected by taste.

Oxygen handling impacts juice chemistry and can be suggested by wine tasting. Broadly speaking, the choices are to either welcome oxygen or to avoid it. Oxygen will oxidize juice phenolics and turn the juice color brown. Brown juice advocates are trying to oxidize phenolics (tannins) to neutralize them ahead of aging and they do that by hyperoxygenation (air bubbling in the juice) and by using low levels of antioxidant (think Chardonnay). When the juice is protected from oxidation, it will stay pale green. Green juice practitioners aim to preserve juice aromatics that are destroyed with oxidation and they do so by hand picking, using full cluster pressing, antioxidant (sulfites), and inert gasses in wine vessels (think Sauvignon Blanc and Riesling).

Juice corrections can be done when the clarified juice is sent to a fermentation vessel. Treatments include adding/removing acidity, adding sugar and yeast nutrients. These additions cannot be tasted unless they are overdone. The fermenting yeasts can be added, or can come from the environment (from a yeast starter for example). It is difficult to be definitive on what yeast is used but, in general, added yeasts lead to aromatically intense and focused wines. Non added yeasts (aka "wild") offer a wider range of population yielding to less focused profiles and, sometime, subtle faults that may be complexing. Good producers understand the pitfalls of each method and it is impossible to taste which one is used unless the winemakers wants us to.

The monitoring of fermentation temperature is critical as it controls fermentation speed, CO2 and aromatic ester production. High temperatures favor ester formation but strip them more readily due to fast CO2 production. Wines that rely on primary aromatics (Sauvignon Blanc) for their quality are fermented at cooler temperatures (8-12C) while more neutral varieties (Chardonnay) are fermented at a warmer 12-20C. It is therefore possible to infer fermentation temperatures (cool, moderate or warm) based on ester intensity and preservation.

The vessels used for fermentation have two types of impact. The first one is the ability to control temperature within the vessel and stainless steel tanks with heating/cooling are the most precise tool for that purpose. The second impact is the penetration of oxygen in the vessel and oak and plastic are the two containers that allow the most oxygen in the wine during fermentation. It is extremely difficult to tease apart the impact of the fermentation vessel on the wine but in general aromatic wines, focused on primary aromas, are made in stainless steel. Neutral wines that, rely on secondary and tertiary aromatics, often are aged in vessels that may add complexity such as oak, plastic, clay, or cement. New oak adds an added layer of toasty aromatics to the wine even during fermentations. Importantly, fermentation in new oak, common for high end Chardonnay, have low levels of vanillin (smells like vanilla just like it sounds) because yeasts metabolize it. Therefore a seamless integration of new oak into a white wine, with low vanillin levels, is often due to the completion of primary fermentation in new oak barrels.

The end of fermentation splits white wines in two categories based on the desired residual sugars (RS). We will discuss sweet wines in the future.

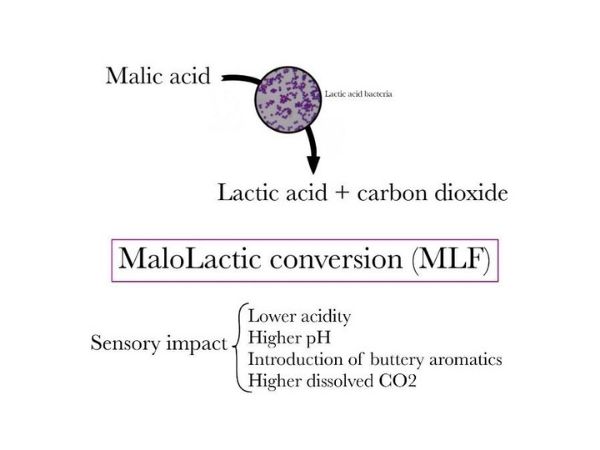

Dry wines with less than 4 g/L RS (often much less) may go through a secondary fermentation (technically it is a conversion since it is done by a bacteria and not a yeast). The conversion is done by lactic bacteria (LAB) and its great benefit is to promote stability by avoiding its occurrence at a later date.

LAB metabolize malic acid into lactic acid, thus the terms "malo lactic fermentation" or "MLF" to name this transformation. MLF has a profound impact on wine by moving the acid profile away from the sharp/sour malic acid (mala=apple in Latin) to the softer lactic acid (lactic=milk). Wine structure is therefore affected (the total acidity goes down and pH goes up) but also aromatics are introduced such as the distinguishable diacetyl that smells like warm butter. MLF can be complete or partial and is easily stopped by adding sulfites and keeping the wines cool. If the MLF is not completed fully, then the wine will have to be sterile filtered prior to packaging to prevent it from to happening in its final container.

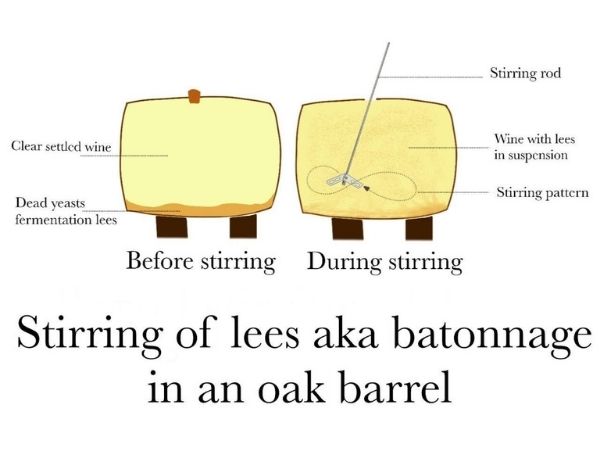

Another decision post primary fermentation, is the retention of fermentation lees (dead yeasts) that are settling by gravity at the bottom of the fermentation vessel. Those dead yeasts can overtime release their content enriching the wine in complex proteins and sugar molecules which increase viscosity and reduce the sharp edges of acidity, astringency and bitterness.

In addition the dead yeast can provide strong aromatics of fermentation which evolve based on the contact length with the lees. Short contact (3 to 6 months) leads to fresh yeast/bread dough aromas that evolve toward cheese rind and yogurt (4 to 8 months) and then go towards nutty, soy sauce aromatics (more than a year of contact). Lees contact requires frequent mixing of the lees to put them back in suspension in the wine in a process known as batonnage which refers to the traditional method of stirring the lees with a wood stick (baton in French). Lees contact can be done in combination with MLF to create extremely complex wines exemplified by the Chardonnay of the Cote d’Or.

There are two factors that matters during aging: its length and the amount of oxygen reacting with the wine which is linked to the vessel used, temperature and the presence of antioxidant. Wine aromatics evolve during aging with primary aromatics slowly decreasing and tertiary aromatics appearing. This evolution happens with time and without the presence of oxygen, therefore thread lightly when guessing for how long a wine was aged before bottling based on this criteria because this gradual aromatic change also occurs in bottle. The oxidation of wine is a function of the type of vessel (new oak and plastic let more oxygen in), how often the vessel is opened, the temperature (heat speeds up oxidative reactions) and the amount of antioxidant (sulfites, phenolics, lees). Broadly, oxidation will mature the wine faster darkening its color and introducing oxidized aromatics such as nutty notes. The evaporation in barrels (poetically called the “angels’ share”) is about 1 to 2% a year and may be detectable if the wine has been aged for more than a year in barrel by the feeling of an increased concentration (including the alcohol).

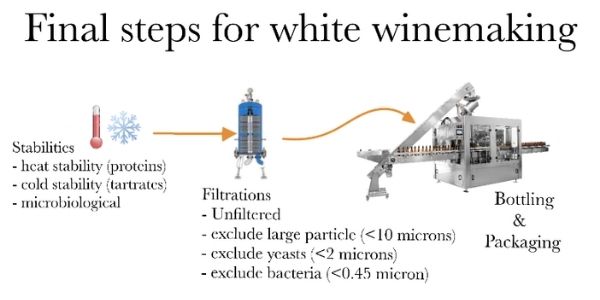

The final stage of white winemaking is the preparation to bottling. Producers worry about stabilities (tartaric, protein, microbiological) and clarity (filtration). Wine tartrates (tartaric acid + potassium or calcium ions) are unstable and precipitate as crystals in cold conditions (which is why treating it is referred to as “cold stability”).

Methods to avoid tartrate deposits include cold precipitation in tank, removing the ions and adding a protecting colloid. These techniques cannot be detected by taste consistently. White wine proteins are unstable and create a haze in warm conditions (which is why treating it is referred to as “heat stability”). The excess protein is removed with a bentonite clay fining (not detected by taste). Microbiological instabilities come from residual "food" in the wine such as sugars (RS) and malic acid. Cold temperature, good hygiene and sulfites are enough to prevent microbial growth at the winery but to guarantee package stability, the wine must be sterile filtered. Wines with no residual food are microbiologically stable and may be filtered for appearance only.

The only pre bottling operation with a clear sensory impact is the adjustment of the level of carbon dioxide (CO2). Wines packaged within 12 months of harvest have excess fermentation CO2 that is adjusted down by chasing it with another gas (nitrogen).

Born in Lyon, France, from a family in the wine business for three generations. Nicolas has a Master degree in winemaking from the University of Dijon, Burgundy and a Master in sparkling winery management from the University of Reims, Champagne. Prior to coming to the United States, have worked in Burgundy and the Rhone Valley as a winemaker.

He came to the United States in 1997 and worked for J. Lohr and The Hogue Cellars as a winemaker. During his time at Hogue Cellars, he went back to school and earned a MBA with honors from the University of Washington (first of class). He was the General Manager and Winemaker for Pacific Rim for 10 years where I lead our two wineries making 600,000 cases of wine. He recently took a position as the Chief Winemaking and Operations Officer for the Crimson Wine Group supervising six prestigious estate wineries in OR, WA and CA. In 2018 he became a Master of Wine formerly joining the prestigious Institute of Masters of Wine.