Educating Sommeliers Worldwide.

By Beverage Trade Network

Sommelier Business joins with Nicolas Quillé, MW to create a short wine technical series to give on-trade professionals wine technical knowledge. In this article we write about Rosé, sparkling and fortified wines basics.

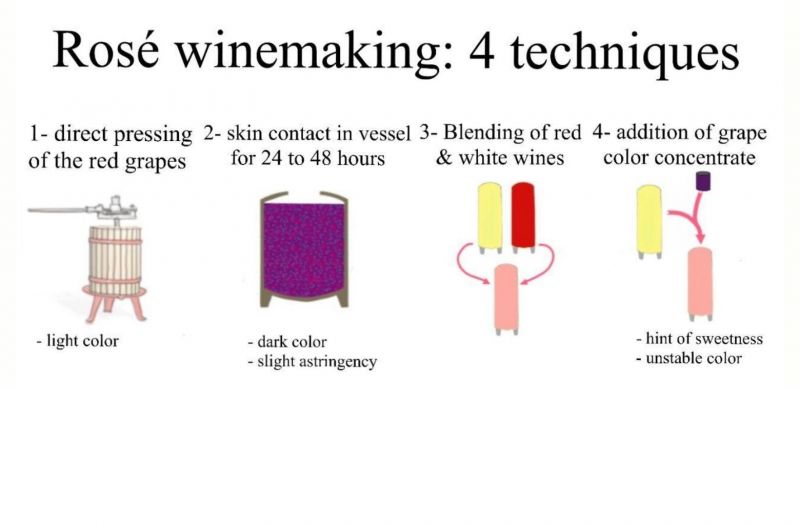

In general, rosé wines have a similar winemaking journey than white wines. The main difference comes from how the pink color happened.

The first way to make rosé is to use the direct press method where red grapes are hand harvested and pressed directly. The contact between skins and juice in the press is sufficient to extract a little color since anthocyanins are water soluble. This method is debatably judged as the most qualitative and leads to palely colored wines and white wine like bodies.

The second method is to press after 24 to 48 hours of skin contact in a wine vessel. The deeply colored juice is then removed from the skin. There is nothing less qualitative about this method except when the grapes were picked with the objective of making a red wine and the rosé wine is simply a byproduct of red winemaking (a rosé of saignée).

The last method is to blend red and white wines together and, as long as the red and white components were intended for that purpose, there is no qualitative consequences – in fact many pink Champagnes are made this way.

Blending tannic red wines with a white wines always result in rosé that are astringent and phenolic. It is worth mentioning that grape color concentrate is used in certain countries to color white wines.

Technically the residual carbon dioxide (CO2) in sparkling wines comes from fermentation. The forced carbonation of wine is mostly prohibited and wine products that are injected with CO2 are labeled “carbonated wines”.

Forcing CO2 into wines always results in bubbles that are large, not well integrated and ephemeral. The most accurate way to predict the final CO2 quantity is to add a measured amount of sugar to a dry wine and to complete a second alcoholic fermentation in a closed container to trap the CO2 (the "prise de mousse"). The CO2 level is directly related to the final pressure through the law of ideal gas.

This process is behind the two most successful methods of sparkling production which are the bottle fermented/traditional method and the Charmat/cuve close method.

The winemaking process before the prise de mousse is similar to any white wine (called "base wine" for sparkling) although sparkling wine grapes are ideally picked early for low sugar and high acidity. This means that the base wines will be fermented, put through MLF or not, aged, and stabilized before the prise de mousse.

The blended base wines are called the "cuvée" and it will be added with sugar/yeast to undergo the prise de mousse in its closed container of choice (tank for Charmat and bottle for traditional method).

Bottle fermentation is the most efficient way to leave the wine in contact (or "en tirage") with the dead yeast for an extended period of time after the prise de mousse. The yeast contact enriches the wine in yeast compounds (a process known as autolysis) that adds body, aromatics (toasted bread, nutty) and that keeps bubble sizes small.

The final step of the sparkling process is to remove the yeasts and to balance the acidity of the finished wine with sugar (dosage). Bottle fermented wines are riddled/shaken to gather the yeast deposit in the bottle neck. The neck is then frozen which traps the yeast deposit in an ice cube that is ejected (disgorgement). Charmat made wines are filtered with a counter pressure filter to retain the CO2 and remove the yeast deposit.

A liquid sugar solution is then added to the wine (dosage). The dosage allows a wide range of final residual sugar levels and it balances the high acidity of sparkling wines.

An alternative to a well measured second alcoholic fermentation is to finish the first alcoholic fermentation fermenting wine in a bottle or a Charmat tank before all the sugars are consumed. The resulting wines are light in alcohol especially if the fermentation is complete. Those wines are labelled methode ancestrale or petillant naturel when finished in bottle. It is far easier to do this method in a Charmat tank as it is done with a Moscato d’Asti.

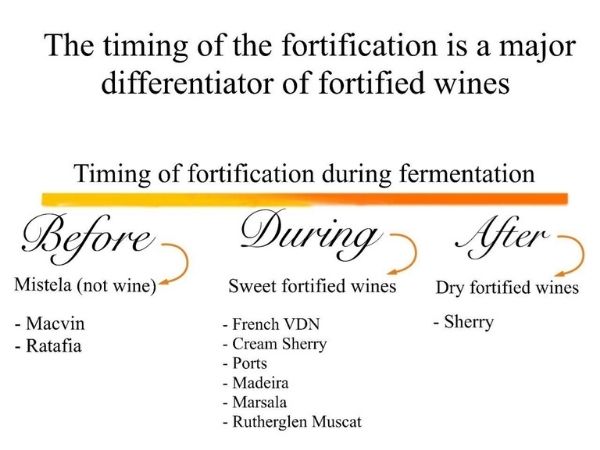

The original idea behind fortification is to increase the alcohol content of the wine making it more stable. The only alcohol that is used is from wine distillation.

One defining stylistic decision is the timing of the fortification and this can be tasted with ease. If the fortification occurs before fermentation then the resulting product is not a fortified wine but a mistela. Mistelas have not fermentation esters and the added alcohol is not well integrated. The fortification can also occur after primary fermentation on a dry wine (a dry sherry for example) or anytime during fermentation which stops it and leaves unfermented residual sugar.

Fortified wines are more resilient and stable due to their higher alcohol content which makes them excellent candidates for long aging. Their natural stability reduces or eliminates the need for sulfites. Fortified wines do not require much stabilization nor filtration especially when they are aged.

How and for how long the fortified wine is aged can be tasted. Aging will change wine color (red going to tawny and whites going to orange/brown) and introduce tertiary notes to the wine such as forest floor or dried nuts. Specifics about each classic fortified wine region will be explored at another time.

Born in Lyon, France, from a family in the wine business for three generations. Nicolas has a Master degree in winemaking from the University of Dijon, Burgundy and a Master in sparkling winery management from the University of Reims, Champagne. Prior to coming to the United States, have worked in Burgundy and the Rhone Valley as a winemaker.

Born in Lyon, France, from a family in the wine business for three generations. Nicolas has a Master degree in winemaking from the University of Dijon, Burgundy and a Master in sparkling winery management from the University of Reims, Champagne. Prior to coming to the United States, have worked in Burgundy and the Rhone Valley as a winemaker.

He came to the United States in 1997 and worked for J. Lohr and The Hogue Cellars as a winemaker. During his time at Hogue Cellars, he went back to school and earned a MBA with honors from the University of Washington (first of class). He was the General Manager and Winemaker for Pacific Rim for 10 years where I lead our two wineries making 600,000 cases of wine. He recently took a position as the Chief Winemaking and Operations Officer for the Crimson Wine Group supervising six prestigious estate wineries in OR, WA and CA. In 2018 he became a Master of Wine formerly joining the prestigious Institute of Masters of Wine.