Educating Sommeliers Worldwide.

By Beverage Trade Network

I started in the restaurant industry at 16. My first job was at a dinner theater in Boulder, Colorado - I was a theatre nerd, and if you bussed tables and ran food during the “dinner” portion, you got to work backstage during the “theatre” portion of the evening. Fast-forward five years and after working as a host and maitre’d, I got my first serving job. I knew literally nothing about wine, but one of the senior servers taught me some basics about how to read people and “sell” (my favorite quote from him is: “people who drink pinot grigio don’t know anything about wine but want to sound like they do”), and on Mondays, there was a wine education hour with one sales rep or another if you wanted to come in early and learn.

In 2012, I essentially got gifted my first sommelier job; I had been working for Danny Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group for a little over three years, and during the opening of North End Grill, they offered me a split schedule - three days as a floor sommelier, and two days as a server. I said yes, started studying, got obsessed with wine theory (I already loved the dance of service), and that was the beginning of everything.

I’m currently the Assistant General Manager of Cote Korean Steakhouse in Manhattan’s Flatiron District; in addition to operations, I also oversee the beverage programs and do the wine buying. Pre-COVID, I was on the sommelier team at Eleven Madison Park for three years.

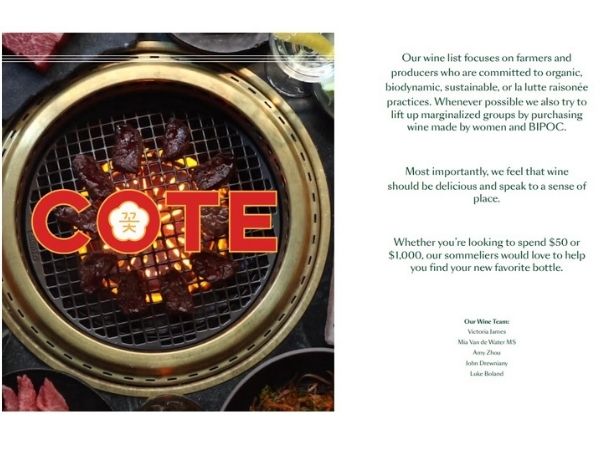

Meet Mia Van de Water promotes organic and wines made by women at Cote along with other great sommeliers.

My focus on the beverage end of the restaurant industry really begins with that first sommelier job in 2012, and I have learned an incredible amount since then, both from the jobs I have held as well as the intense studying I did while moving through the various levels of the Court of Master Sommeliers exams. Some highlights below, in no particular order:

From my tenure at North End Grill, where I went from floor sommelier to Beverage Director, and which was a restaurant that underwent a roller-coaster evolution both operationally and financially during my five years there, I learned the value of creativity in curation. Your beverage programs need to have a point of view that is tied into the identity of the restaurant (not necessarily your personal preferences), and that actively exhibits value to your guests while remaining accountable to your budget. This requires critical, innovative thinking, as well as a deep understanding of what drives your guests. I also learned that to get the budget latitude that you want, you need to be able to speak to your financial team in terms they understand spreadsheets.

From working at Eleven Madison Park, I gained a deeper understanding of how to build a wine pairing so that it is a journey of its own, not just a complement to the food. I also had the priceless experience of regularly selling the greatest wines in the world at various stages of maturity, which makes one sound like a total snob to everyone else, but provides irreplaceable insight into what makes a wine truly great, regardless of price.

From competing around the world (through the Chaîne de Rôtisseurs), and traveling with sommeliers from other countries, I learned that styles of sales and service are not universal. Especially living in a market like New York, we tend to think that we do everything better than everyone else, but in truth, every guest is going to be comfortable with a slightly different tableside presence and language, and to be a truly great sommelier is to be able to adjust yourself seamlessly to be the version of yourself that will make that guest most comfortable.

From the rigorous level of subject mastery required to pass the Master Sommelier exam, I learned that the most important question we must all ask ourselves is “why?” Memorizing tens of thousands of random facts about wine law and geography and climate means nothing (and is much more difficult!) if you don’t build an understanding of how all of these factors work together. I also learned that no matter what country you are studying, you can find something exciting and interesting about it. There are wine-producing regions and countries that I never would have bothered to learn about without the imperative of the MS exam, and I would be a lesser sommelier and service professional if I had not poured time and energy into a deeper understanding of these places and why they inspire passion in other drinkers.

Meet Mia Van de Water - Master Sommelier

In the States, we were already heading this way, but - you cannot just be a sommelier, ever. I firmly believe that as a sommelier, you should be the best service professional on the floor; you should be able to do every job in the restaurant as well or better than the person who does it daily. Sommeliers should be involved with and curate every aspect of a guest’s experience, not just pop in to pour a pairing or sell a fancy bottle. Now, more than ever, there is no budget for that. I also firmly believe that as wine professionals, we have the most potential to positively impact the bottom line of the restaurant. You can only charge so much for food, and so much for cocktails, and the prime cost of both of those revenue categories is quite high. But you can drive up check averages substantially with a healthy wine program, and you can build a program that brings guests in as much as the food does. We have enormous potential to help save our businesses, and we need to leverage our financial savvy to do that.

You must be able to execute all aspects of service, period. If you cannot captain a table - reading the guests, building a relationship, guiding them through the menu, making thoughtful suggestions to enhance what they are interested in - you have no business trying to sell wine. You also must know how to sell. Academic knowledge about wine does not sell bottles (although you certainly need to have that knowledge as a foundation); instead, our job is to listen, ask questions, translate whatever wild thing the guest says about their preferences (“I like a lighter red, like Cabernet Sauvignon”), and come up with the right wine at the right price for that guest in that moment. And you must understand how your financials work.

The biggest shortcoming for our industry (at least in America) is that it is extremely difficult to learn how the back end of your program works. Most sommeliers count inventory and that’s it. Then they get a Wine Director job and all of a sudden they’re expected to understand how to fix it when the numbers are out of line, or how to hit both budgeted sales and COGS if those numbers are both wildly aspirational. I was incredibly lucky in my first Wine Director job to have a Corporate Wine Director (John Ragan MS) who was incredibly savvy and detail-oriented, and a General Manager (Kevin Richer) who understood the ins and outs of the whole operation, and could give me advice (step-by-step if necessary) anytime I needed it.

Most people don’t have that. And in the worst cases, the wine directors aren’t even read into the P&L by the operations team, which means all that potential for really leveraging the program to build sales and covers is totally dismissed.

A) Does it make sense conceptually for the program and the venue? B) Does it present excellent quality for the price? C) Is it delicious? D) Can I afford it?

You can follow her on Instagram and connect with her there.

For wine, it really depends on what I’m doing and who I’m doing it with - I drink different wines when visiting my mother than when hanging out with my former EMP colleagues - but mostly mineral-driven whites and lighter, unoaked reds. If I’m out at a restaurant, either I’ll choose the wine for the food or build a menu around wines that are particularly exciting on the list; it can go either way. Outside of wine - spritzers, negronis, 50/50 gin martinis (or particularly good Gibsons), scotch, and amaro. And cheap beer.

Put effort into building the front and back ends of the experience - glasses of champagne, glasses of dessert wine, etc. (this is a great area for education and sales contests for server teams, too!). Always offer more, even if you think a guest will say no (although obviously not if you are concerned a guest is dangerously intoxicated). Sell at the price point your guest wants to spend, don’t aggressively upsell - the guest that comes once a week and buys a $75 bottle of wine with dinner is much better for your restaurant than the guest that comes once and buys a $500 bottle. But if you get a guest who clearly likes to spend (you know, the guy who says “do you have any Sassicaia?” or “I was thinking about starting with Krug”), shoot your shot high.

We do an enormous amount through Instagram - it seems to be the most direct line to our guests these days. Put some high profile loss leaders out there - if a guest who loves Kistler see that your price is $30 cheaper than everyone else’s, they’ll remember it (and use your data to make these decisions - if your median average bottle price on white wine is $70, selling Kistler at $120 instead of $160 will make you more money in the long run as people will want to cash in on the “deal” - if your median average is already $150, find something else recognizable at $250 and drop the price on that). Create specials with wine that drive cover counts on nights that are historically slow - for example, at North End Grill we would do Buy One, Get One on bottles of wine on Sunday nights to get people to come in with friends instead of cooking dinner at home. Think creatively about what would appeal to your clientele, in your neighborhood. And make sure it’s on-brand - whatever you do should fit in seamlessly with the identity of the restaurant and the program you’ve already established.